Chapter 7

Lessons we could have learnt from other landslides

7.1 Landslides in Victoria

- Landslides that result in injury and property damage of the kind experienced in McCrae in January 2025 are not common in Victoria, but they are also not unprecedented.

- Landslides have been a natural occurrence in the evolution of Victoria’s landscape over millions of years. A range of factors have minimised their frequency, severity and impact. These include lower population density in mountainous and erosion-prone areas and the use of land planning controls.

Prior to 2000, some of the most notable impacts from landslides in Victoria included:

- loss of a house and animals, and damage to a road at the now Dandenong Ranges National Park (1891);1

- road damage at Narracan in Gippsland (1934);2

- destruction of critical infrastructure and agricultural lands, and disruption to the East Barwon River for 14 months resulting in the formation of a new lake – Lake Elizabeth in the Otway Ranges (1952);3

- loss of a house at Calignee and the isolation of the farming township of Le Roy in South Gippsland (1952);4

- destruction of bridges, the town pool and construction work in Walhalla in Gippsland (1952);5

- hiatus of the Puffing Billy railway for nine years at Gembrook (1953);6

- damage to housing, property, roads and infrastructure at Wye River on the Great Ocean Road (1964);7 and

- loss of two lives and several injured at Lal Lal Falls Reserve Ballarat (1990).8

Details about historical landslides in McCrae are set out in Chapter 3 of this Report.

- Over the last two decades, urban growth and infrastructure development, coupled with a changing climate, have added new complexities to landslide management in Victoria.

- Three recent Victorian landslides stand out for their significant economic, social and/or environmental impacts: the Yallourn Mine landslide in 2007, the Grampians landslides in 2011 and the Great Ocean Road landslides in 2016.

- Reviews and Inquiries into those emergencies found common challenges and opportunities for policy, regulatory and planning reform. Due to funding, time and/or circumstance, many of those challenges still exist today and the opportunities for reform remain unaddressed. These are discussed further below but largely relate to the:

- importance of collating better data, modelling and monitoring in respect of landslide risk in Victoria;

- need to share information about landslide risk with stakeholders and communities to support informed decision-making, and to strengthen preparedness for landslides;

- need to better manage the landslide risk associated with water management including the management of groundwater and stormwater, particularly given the compounding impacts of climate change and severe weather;

- importance of applying land use planning controls to manage landslide risk; and

- importance of retaining corporate knowledge, capability and insights about landslide risk, from lived experience and lessons learnt, through to historical decisions about risk management in service and infrastructure design and delivery.

Yallourn Mine landslide in 2007

- In 2007, electricity supply was disrupted across Victoria when a landslide occurred at the Yallourn East Field Mine. The landslide led to six million cubic metres of coal and soil, spanning over 500 metres in length, travelling down an 80 metre slope, causing the Latrobe River to flood the mine.9 The State of Victoria appointed a Mining Warden to lead the Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry in order to establish the circumstances surrounding, and causes of, the landslide, and to examine any mine safety issues and make recommendations to prevent or minimise the risk of similar events occurring in the future.

- As in McCrae, water played a key role in the Yallourn landslide. The Yallourn Mine Batter Inquiry identified the principal cause of the landslide as water pressure in a naturally occurring joint connected with the Latrobe River, and water pressure in interseam clays underlying the block of coal. Water pressures created a buoyancy effect on the block of coal, reducing resistance to sliding along its base.10 There were also early signs of an impending slope failure at Yallourn, including visible cracking and subsidence, as well as monitoring data indicating imminent failure. However, unlike in McCrae where there was expert advice ahead of the 2022 landslides that the area was susceptible to landslides, the signs were not interpreted correctly at Yallourn and external consulting advice was provided that a catastrophic failure was unlikely on the day of the Yallourn landslide.11

- Importantly, the Yallourn Inquiry found that “this failure was not new or unusual and is the principal mechanism of batter failure in the Latrobe Valley Mines”.12 It noted that changes to the Yallourn East Field Mine’s layout over time and the implementation of new mining methods had also resulted in key components of the mine’s slope design (which ensured its stability) no longer being applied. It found that technical expertise and corporate knowledge about risks had been lost over time or were no longer properly appreciated in the years prior to the failure, and that strategies were needed to better capture knowledge and historical experience in new and evolving models of risk management.13

- Many of the Yallourn Inquiry’s recommendations are still relevant to landslide management more generally. The Yallourn Inquiry recommended coal mines improve groundwater and surface water control, as well as hydrogeological and geotechnical models, and their application in planning and system design. A multidisciplinary approach to planning was deemed necessary to address the many competing demands at play in managing risk and mining operations.14

Grampians (Gariwerd) National Park landslides in 2011

- In January 2011, an intense rainfall event in Western Victoria triggered over 200 landslides in the Grampians (Gariwerd) National Park and caused widespread regional flooding. Three arterial roads were closed for several months, urban and agricultural water supplies were impacted, and there was damage to cultural heritage sites, pavements, culverts, drains and bridges. Public and private property was damaged by boulders, trees, debris and mud.15 Given the significance of the landslides, the Northern Grampians Shire and partners, including the Victorian Department of Justice, commissioned Federation University Australia to research the social, economic and environmental impacts of the disaster, with a specific focus on addressing landslide risk and the community’s resilience to it.16

- The Federation University Report, Understanding the 2011 Grampians Natural Disaster, addressing the risk and resilience, found the disaster had a deep and enduring impact on the local community. While no lives were lost, stress and anxiety were ongoing issues within the community. The region also experienced substantial economic losses, particularly loss of income through reduced tourist activity and disruption to normal trading. The cost of reconstruction for the State was considerable. It involved rebuilding and restoring structures and assets across private and public land, at an estimated cost of approximately $140 million.17

- Much like McCrae, the areas impacted in the Grampians were not covered by the Council’s existing EMO despite past recognition by the Council of the need for the EMO to cover those areas. It was recommended that the EMO be extended to ensure statutory planning controls were applied to the landslide susceptible regions of the Grampians Shires, adopting the methods of the Australian Geomechanics Society National Landslide Risk Management Framework.18

- The Federation University Report also highlighted challenges and opportunities for reform, including improvements in maintaining landslide risk data and planning in landslide management.19 It contained important insights in respect of public education programs for all hazards.

Great Ocean Road landslides in 2016

- Similar to the Grampians, where floods and landslides became part of a complex emergency event, communities along the Great Ocean Road between Separation Creek and Wye River experienced extensive landslides following bushfires in 2015. The VicSES estimates that over 180 landslides occurred in that area.20

- The Review of the Wye River and Separation Creek Fire Recovery, commissioned by Emergency Management Victoria, and led by Nous Group, considered management of the landslides during the recovery efforts. The Review found that there were extensive challenges to and breakdowns in communications between local and state government agencies, including but not limited to the Country Fire Authority, Emergency Management Victoria, the Environment Protection Authority and VicRoads, and with the community during the landslides which “left the community feeling poorly informed, anxious and overlooked”.21 It recommended that agencies involved in the management of landslides develop a more flexible approach to community engagement and consider their governance and culture to ensure their organisational structures could accommodate the concurrent demands of response and recovery.

- The Great Ocean Road Taskforce Report, Protecting our Iconic Coast and Parks, also emphasised the need for action in relation to landslide management. It identified the challenges of land instability and subsidence, cliff regression, undercutting and coastal erosion as critical issues for the region. It noted that these were likely to be further exacerbated by climate change and increasingly frequent, severe and complex weather events.22 The result would be wide-reaching, with impacts on infrastructure, the economy and the environment. The Victorian Government went on to commit $53 million “to safeguarding the geotechnical future of the road following the 2016 floods and landslides at Separation Creek and Wye River”.23

- The Great Ocean Road landslides reaffirmed the importance of strong planning and mitigation measures where underlying geological, engineering and topographical characteristics can lead to landslides. Climate change creates an imperative for planning and mitigation, when underlying contributing factors can be compounded by extreme weather events.

7.2 Lessons from interstate and overseas

- Landslides causing widespread social, economic and environmental consequences have been infrequent in Australia but when they have occurred, they have had an enduring impact on local communities and provided long-term lessons for disaster risk management. Between 2000 and 2011, 24 people died and 100 people were injured in Australia as a result of landslides.24

- While every context is different, past events both interstate, and overseas, have offered important insights into managing landslide risk that are relevant to this Board of Inquiry. Coronial findings and recommendations aimed at strengthening regulatory responsibility, mitigation policy and planning have been considered by this Board of Inquiry and have been instrumental in framing its work. Insights include the significance of water management and infrastructure maintenance, the importance of emergency management planning, and failings in accountability and leadership.

- Failings in water management and infrastructure maintenance were identified as either a primary or secondary cause in the:

- deaths of two people in their home following the collapse of the Coledale rail embankment in 1988;25

- cliff collapse at Gracetown, Western Australia in 1996 where rainfall was found to be the cause of a saturated cliff overhang collapsing above school students and staff who were sheltering underneath, leading to the deaths of nine people;26 and

- deaths of five people in a landslide at the Old Pacific Highway in Somersby, which the Coroner found to have been caused by the local Council’s inadequate road maintenance which led to a collapsed water culvert.27

- Water management and infrastructure maintenance were also critical factors in the tragic landslide at Thredbo Village in Alpine New South Wales in July 1997. This event caused 18 deaths and the destruction of two ski lodges. As with the events in Coledale and Somersby, water saturation, maintenance, building and planning failures were identified as factors or causes of the landslide. Notwithstanding geotechnical, planning and engineering failures, the New South Wales State Coroner investigating the Thredbo Village landslide – Coroner Hand – found the primary causes of the landslide to be:

- the failure of any government authority responsible for the care, control and management of Kosciusko National Park and the maintenance of the Alpine Way to take any steps to ensure Thredbo Village was rendered safe from exposure to the marginally stable embankment;

- the approval and construction of a water main made of materials which could not withstand the conditions (movement taking place in the Alpine Way embankment); and

- leakage from that water main that saturated the soil.28

- Importantly for this Board of Inquiry, Coroner Hand also made a range of recommendations to strengthen landslide risk management in relation to land use planning, building controls and emergency management.

- With respect to emergency management, Coroner Hand found that the local disaster plan did not take into account the risk of landslides in the Alpine area. He recommended that “both District and Local Disaster Plans (DISPLANs) be revised, taking into account the risk of landslides in the area and their management”.29

- Coroner Hand also recommended the Building Code of Australia and any local code dealing with planning, development and building approval procedures be reviewed and amended to require relevant authorities to take into account and apply proper hillside building practices and geotechnical considerations when assessing and planning urban communities in hillside environments.30 At the time, Coroner Hand noted there was no detailed system requiring the submission and consideration of geotechnical or other engineering reports that took into account the difficulties of building in a steep alpine environment.

- The Thredbo Coronial Inquest otherwise led to widespread national reform of landslide management.

- In 1998, Engineers Australia and the AGS formed a Taskforce on the Review of Landslides and Hillside Construction Standards, which concluded that existing codes and standards were inadequate. It recommended creating four new guidelines for:

- landslide hazard zoning for urban areas, roads and railways;

- slope management;

- site investigations, design, construction and maintenance; and

- landslide risk assessment.31

- Further improvements were made to the guidelines in 2000 and 2002.32

- In 2003, the Commonwealth Government introduced the National Disaster Mitigation Program, which funded the AGS and local governments to undertake further research into the likelihood of landslides, and to develop zoning and slope management guidelines as well as a Practice Note.33 These were peer reviewed and completed in 2007.34

- In addition, other government entities, the subject of findings in the Thredbo Coronial Inquest, developed tools to manage landslide risks. New South Wales Transport, Roads & Maritime Services produced guidelines for slope asset management and natural disaster slope damage restoration requirements which have continued to be updated over time.35

The international experience

- There are many countries and regions with far more extensive experience with significant landslides than Australia. However, many of the challenges in managing landslide risk are similar.

- A review of significant landslides internationally highlights that water management, road maintenance, planning and development in mountainous and coastal areas are critical factors in managing vulnerability and exposure to landslides, and are relevant elements in landslide risk management.

- Further, climate change presents new, complex challenges leading to increased risk through the greater frequency and/or magnitude of heavy rainfall and shifts in the location and periodicity of heavy rainfall.36

- Individual country efforts to better understand the risks and design mitigations, and develop and implement engineering approaches, are being pursued through a range of cooperative arrangements such as the Kyoto 2020 Commitment for Global Promotion of Understanding and Reducing Landslide Disaster Risk.37 The Kyoto 2020 Commitment sets out that:

Human intervention can make a greater impact on exposure and vulnerability through… land use and urban planning, building codes, risk assessments, early warning systems, legal and policy development, integrated research, insurance, and, above all, substantive educational and awareness-raising efforts by relevant stakeholders.

Kyoto 2020 Commitment for Global Promotion of Understanding and Reducing Landslide Disaster Risk.38

- These international partnerships offer important insights into understanding how we can mitigate the risk of landslides into the future and have assisted to inform the Board of Inquiry’s findings and recommendations.

Chapter 7 Endnotes

- 1 Museums Victoria, ‘Item BA 1657 Lantern Slide – Landslip, Dandenongs, Victoria Jul 1891’, Museums Victoria Collections (Web Page) https://collections.museumsvictoria.com.au/items/1449178.

- 2 Public Record Office Victoria, ‘34_00059_B Allambee-Childers Road: landslide caused by heavy rainfall’, Photographic Collection, Master Negatives and Digitised Images (VPRS17684) (Record) https://prov.vic.gov.au/archive/A1D63F94-FAC7-11EA-BE8C-AB441AA0DA39/co….

- 3 ‘Big Victorian Landslide Forms Lake, Endangers Four Towns’, Sydney Morning Herald (New South Wales, 23 June 1952) 1 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/18269952.

- 4 ‘Victorian Landslides’, Border Watch (Mount Gambier, 26 June 1952) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/78668744

- 5 ‘Walhalla hit again by landslides, flood’, The Sun News (Melbourne, 13 December 1952) 11 https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/279919417.

- 6 Victoria, Parliamentary Debates, Legislative Council, 5 April 2022 (Cindy McLeish VLA, Member for Eildon).

- 7 P G Dahlhaus, A S Miner, W Feltham and T D Clarkson, ‘The impact of Landslides and erosion in the Corangamite Region Victoria, Australia’, (Paper number 479, IAEG2006, Centre for eResearch and Digital Innovation) 8 https://www.ccmaknowledgebase.vic.gov.au/kb_resource_details.php?resour….

- 8 P G Dahlhaus, A S Miner, W Feltham and T D Clarkson, ‘The impact of Landslides and erosion in the Corangamite Region Victoria, Australia’, (Paper number 479, IAEG2006, Centre for eResearch and Digital Innovation) 8 https://www.ccmaknowledgebase.vic.gov.au/kb_resource_details.php?resour….

- 9 Parliament of Victoria, Mining Warden – Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry (Final Report, 30 June 2008) i.

- 10 Parliament of Victoria, Mining Warden – Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry (Final Report, 30 June 2008) i.

- 11 Parliament of Victoria, Mining Warden – Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry (Final Report, 30 June 2008) 96.

- 12 Parliament of Victoria, Mining Warden – Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry (Final Report, 30 June 2008) i.

- 13 Parliament of Victoria, Mining Warden – Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry (Final Report, 30 June 2008) 95, 104.

- 14 Parliament of Victoria, Mining Warden – Yallourn Mine Batter Failure Inquiry (Final Report, 30 June 2008) 103–104.

- 15 Federation University Australia, Centre for eCommerce and Communications, Understanding the 2011 Grampians Natural Disaster, addressing the risk and resilience (Final Report, 31 March 2014) 38.

- 16 Federation University Australia, Centre for eCommerce and Communications, Understanding the 2011 Grampians Natural Disaster, addressing the risk and resilience (Final Report, 31 March 2014) iii.

- 17 Federation University Australia, Centre for eCommerce and Communications, Understanding the 2011 Grampians Natural Disaster, addressing the risk and resilience (Final Report, 31 March 2014) 34.

- 18 Victoria State Emergency Service, State Landslide Hazard Plan (Version 1, September 2018) 6.

- 19 Federation University Australia, Centre for eCommerce and Communications, Understanding the 2011 Grampians Natural Disaster, addressing the risk and resilience (Final Report, 31 March 2014) vii–viii.

- 20 Victoria State Government – Great Ocean Road Taskforce, Protecting Our Iconic Coasts and Parks: Governance of the Great Ocean Road, its land and seascapes (Final Report, August 2018) 33–34.

- 21 Nous Group, Review of the Wye River and Separation Creek Fire Recovery (Review, 2 June 2017) 38–39.

- 22 Victoria State Government – Great Ocean Road Taskforce, Protecting Our Iconic Coasts and Parks: Governance of the Great Ocean Road, its land and seascapes (Final Report, August 2018) 33–34.

- 23 Victoria State Government – Great Ocean Road Taskforce, Protecting Our Iconic Coasts and Parks: Governance of the Great Ocean Road, its land and seascapes (Final Report, August 2018) 13.

- 24 Marion Leiba, ‘Impact of Landslides in Australia to December 2011’ (2013) 28(1) Australian Journal of Emergency Management 28, 30.

- 25 Derrick Hand (New South Wales State Coroner), Report of the inquest into the deaths arising from the Thredbo landslide (Report, 29 June 2000) 51 [219].

- 26 Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience, ‘Landslide – Gracetown, Western Australia’, Australian Disaster Resilience Knowledge Hub (Web Page) https://knowledge.aidr.org.au/resources/landslide-gracetown-western-aus….

- 27 ‘Inquest Found Council Responsible For Family’s Death’, Government News (online, 19 September 2008) https://www.governmentnews.com.au/inquest-found-council-responsible-for….

- 28 Derrick Hand (New South Wales State Coroner), Report of the inquest into the deaths arising from the Thredbo landslide (Report, 29 June 2000) 5 [5].

- 29 Derrick Hand (New South Wales State Coroner), Report of the inquest into the deaths arising from the Thredbo landslide (Report, 29 June 2000) 192 [929].

- 30 Derrick Hand (New South Wales State Coroner), Report of the inquest into the deaths arising from the Thredbo landslide (Report, 29 June 2000) 190 [919].

- 31 Australian Geomechanics Society Landslide Zoning Working Group, ‘Guideline for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land use planning’ (2007) 42(1) Australian Geomechanics Journal 13, 13. https://australiangeomechanics.org/admin/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/LRM…

- 32 Australian Geomechanics Society Landslide Zoning Working Group, ‘Guideline for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land use planning’ (2007) 42(1) Australian Geomechanics Journal 13, 13.

- 33 Bruce Walker, Warwick Davies and Grahame Wilson, ‘Practice Note Guidelines for Landslide Risk Management’ (2007) 42(1) Australian Geomechanics Journal 69.

- 34 Australian Geomechanics Society Landslide Zoning Working Group, ‘Guideline for landslide susceptibility, hazard and risk zoning for land use planning’ (2007) 42(1) Australian Geomechanics Journal 13, 14.

- 35 New South Wales Transport Roads & Maritime Services, AM21 Guidelines for slope asset management (Guidelines, Version 4.0, 1 July 2019); Transport for New South Wales, Guide for Natural disaster slope damage restoration requirements (Guidelines, September 2023).

- 36 International Consortium on Landslides, ‘The Kyoto Landslide Commitment 2020’, International Programme on Landslides (Web Page) https://www.landslides.org/ipl-info/the-kyoto-landslide-commitment-2020/.

- 37 International Consortium on Landslides, ‘The Kyoto Landslide Commitment 2020’, International Programme on Landslides (Web Page) https://www.landslides.org/ipl-info/the-kyoto-landslide-commitment-2020/.

- 38 International Consortium on Landslides, ‘The Kyoto Landslide Commitment 2020’, International Programme on Landslides (Web Page) https://www.landslides.org/ipl-info/the-kyoto-landslide-commitment-2020/.

Chapter 8

Improving landslide management in Victoria

8.1 Lessons learnt from McCrae

- This Chapter addresses the regulatory framework in relation to the prevention and management of landslides in Victoria.

- Landslides are one of many hazard types managed within Victoria’s emergency management system. However, they do not receive the same level of attention within the system as other natural hazards, such as bushfires and floods. This is likely because, historically, landslides have not affected Victorians as often or as severely as these other events.

- The recent landslides in McCrae have underscored the significant impact that landslides can have on a community, and have revealed opportunities for system-wide improvements in both emergency management and land planning.

8.2 Emergency management

An overview of Victoria’s emergency management system

- Victoria’s emergency management system seeks to create safer and more resilient communities by:

- minimising the likelihood, effect and consequence of emergencies, such as landslides, on communities and the environment;

- establishing efficient governance arrangements that create accountability, enable cooperation and foster community and industry participation; and

- delivering people-centred programs and services that support communities to be prepared and recover well after emergencies such as landslides.1

- Emergency Management Victoria is a central body for emergency management in Victoria.2 It is established under the Emergency Management Act 2013 (Vic) (Emergency Management Act) and is responsible for the governance and coordination of emergency management arrangements.3

- Emergency Management Victoria consists of a Chief Executive and the Emergency Management Commissioner. The Commissioner has the function of preparing the SEMP, which outlines the framework for Victoria’s emergency management system.4

- The SEMP provides for an emergency management system that uses common management arrangements to respond to all forms of emergency.5 This approach, known as the “all-emergencies” or “all-hazards” approach, is the result of a decade of reform and learnings from a diverse range of events such as the Black Saturday Bushfires in 2009, thunderstorm asthma events and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The SEMP provides for the mitigation of, response to and recovery from emergencies (before, during and after), and specifies government agencies’ roles and responsibilities for emergency management.

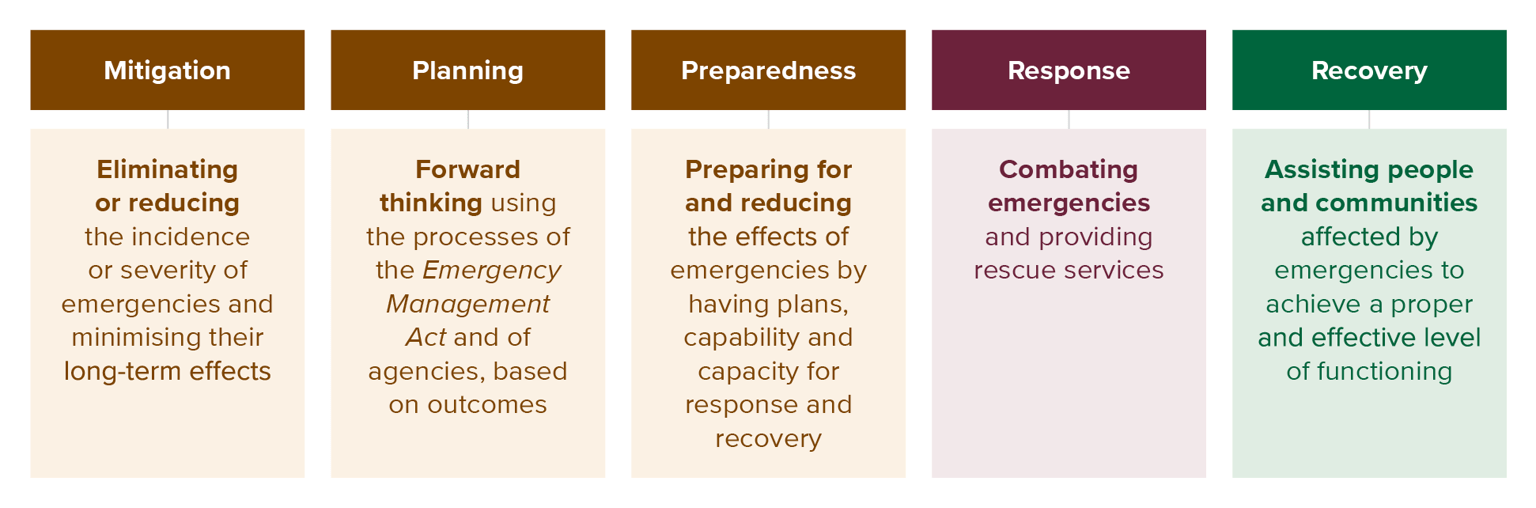

- As shown in the diagram below (Figure 8.1), there are five phases in emergency management.6

- The first phase is mitigation, this concerns the elimination or reduction of the incidence or severity of emergencies and the minimisation of their effects.7 The SEMP provides that both within and outside the emergency management sector, government agencies contribute to the mitigation of emergencies as part of their business-as-usual functions. For example, they mitigate emergencies by:

- formulating and implementing policy and regulation (such as land-use planning and building regulations); and

- building, operating and maintaining infrastructure.8

- The second phase is planning, this concerns the documentation of emergency management at state, regional and municipal level.9

- The third phase is preparedness. This includes the activities of government agencies to prepare for and reduce the effects of emergencies by having plans, capability and capacity for response and recovery.10

- Once an emergency or hazard has eventuated, it triggers the response and recovery phases respectively. According to the SEMP, response is the action taken during, and in the first period after, an emergency to reduce the effects and consequences of the emergency on people, their livelihoods, wellbeing and property; on the environment; and to meet basic human needs.11 Recovery is the assisting of persons and communities affected by emergencies to achieve a proper and effective level of functioning.12

- The SEMP outlines government agencies’ roles and responsibilities in the different phases of emergency management.

- In the mitigation phase, the agencies are responsible for their business-as-usual activities such as maintaining infrastructure and mitigation activities for specific emergency risks.13 Specific emergency risks are those assessed as significant for the State in the Emergency Risks in Victoria Report (2023). Under each emergency risk, the report identifies relevant mitigation activities and the agencies involved.

- In relation to the response phase, the SEMP nominates a control agency for specified forms of emergency. Control agencies are responsible for coordinating actions for a specific emergency and establishing management arrangements for an integrated response to the emergency.14 Agencies are also nominated to participate in a supporting role in response activities.15

- Finally, in addition to providing for the SEMP, the Emergency Management Act also provides for the preparation of emergency management plans at regional and municipal level.16 All emergency management plans must contain provisions for the mitigation of, response to, and recovery from, emergencies and specify the roles and responsibilities of agencies in relation to emergency management.17

How are landslides managed in the emergency management system?

SEMP

- The first observation to make is that the SEMP currently gives less attention to landslides than it does to other hazards, such as bushfires, earthquakes, floods and storms.

- The following key features are noted:

- the control agency nominated in the SEMP for managing the emergency response to landslide events is the VicSES;18

- no participating agency is nominated for mitigation activities because landslides were not assessed as a significant state emergency risk in the Emergency Risks in Victoria Report (2023);19

- the VicSES’s table of mitigation activities for emergencies in the SEMP contains one reference to landslides. It is as follows:

Increase individual capacity and capability of the community to prepare and respond by engaging with communities providing storm, flood, earthquake, tsunami and landslide risk information, community education and engagement.20

d. similarly, the VicSES’s table of recovery activities for emergencies in the SEMP contains a single reference to landslides. It is as follows:

Support the Controller by providing assistance and advice to individuals, families and communities who have been affected by flood, storm, tsunami, earthquake of landslide.21

- There are no other specific references to roles and responsibilities for landslides in the SEMP.

- It is, however, important to note that under the SEMP a range of agencies, including municipal councils and water authorities, have general roles and responsibilities for emergency management. These range from providing community warnings and developing municipal emergency plans, to infrastructure maintenance, and providing relief and recovery services. The SEMP provides that:

shared responsibility in emergency management is everyone’s business. Individuals, communities, organisations, businesses, all levels of government and the not-for-profit sector all have a role to play in planning for, responding to and recovering from emergencies.22

- The most striking feature of those noted above, and which requires further discussion, is that landslides were not assessed as a significant state emergency risk in the Emergency Risks in Victoria Report (2023), which had consequences for the SEMP. Landslides were also not identified in the earlier version of the Report published in 2020.23

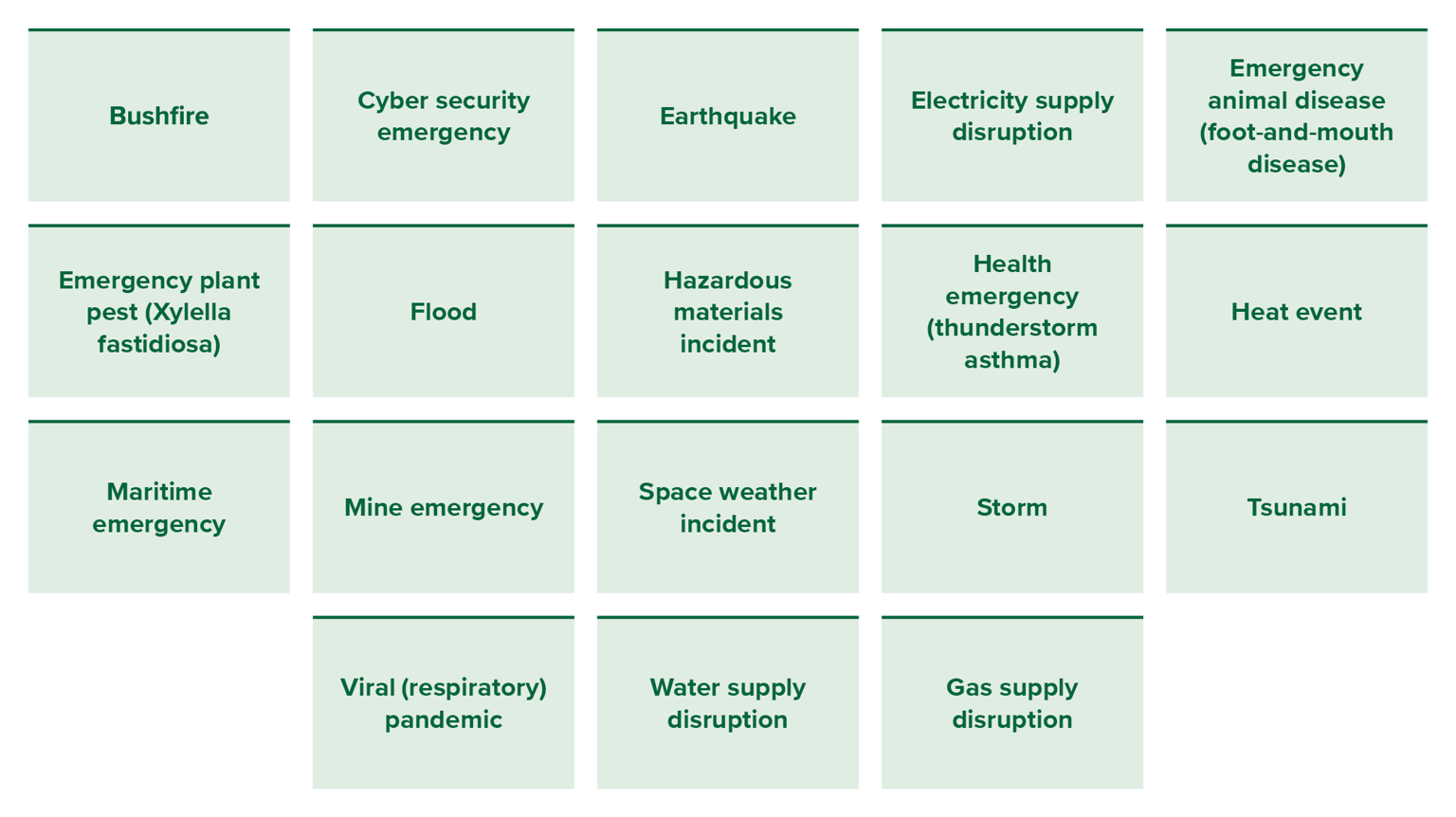

- The 2023 Emergency Risks in Victoria Report (2023) identifies 18 state-level emergency risks.24 They are identified below:

- These 18 state-level emergency risks were identified using the Victorian Emergency Risk Assessment methodology adopted from the National Emergency Risk Assessment Guidelines.25

- Using that methodology, landslide risks did not meet the criteria for inclusion.26

- This is surprising given Victoria’s landslide history over the past decade, as detailed in Chapter 7, and considering the other risks identified above. It is notable that landslide is included in the Queensland State Disaster Risk Report (2023),27 and in New South Wales’ State Disaster Mitigation Plan.28

- Though the reason for its omission in Victoria is unclear, the Board of Inquiry understands that steps have now been taken to address the issue. These steps are described below.

- Emergency Management Victoria recently engaged the VicSES to coordinate a risk identification and scoping workshop.29 Workshops were held on 24 June 2025 and 12 August 2025.30 Following those workshops, landslide has now been given an overall risk rating of extreme.31

As a result, the VicSES is now set to develop a landslide sub-plan to the SEMP, which includes articulating roles and responsibilities and outlining the emergency management arrangements for mitigation, response (including relief) and recovery.32

Recommendation 17: The SEMP and the landslide sub-plan to the SEMP The Board of Inquiry recommends the Victoria State Emergency Service (the VicSES) progress the development of a landslide sub-plan to the SEMP.

In this context, it is also recommended the Emergency Management Commissioner consider consequential amendments to the SEMP, including making water corporations and local councils participating agencies for landslide mitigation activities, such activities should include the:

a. identification of landslide risk;

b. development of operational and maintenance plans and processes for water assets; and

c. sharing of information between water corporations and local councils to assist in the identification of landslide risk and the management of water assets.

Recommendation 18: Landslide training and education programs The Board of Inquiry recommends Emergency Management Victoria, the VicSES, and the Inspector-General for Emergency Management update existing training and education programs to incorporate and reflect the development of the landslide sub-plan and any related amendments made to the SEMP.

Regional and municipal emergency management plans

- As noted earlier, in addition to the SEMP, there are emergency management plans at the regional and municipal level.

- McCrae is captured by the Southern Metro Regional Emergency Management Plan.33 Like the state plan, it does not currently recognise landslides as a significant risk.

- At a municipal level, the council of each municipal district must establish a municipal emergency management planning committee.34 It is that committee which prepares the emergency management plan for the municipality.35

- The Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Planning Committee is the committee relevant to McCrae. It currently comprises representatives from the Shire, Victoria Police, the VicSES, Fire Rescue Victoria, the Country Fire Authority, the Australian Red Cross, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing, Department of Health, Forest Fire Management Victoria, the Mornington Community Support Centre, Focus Life Disability Services and Ambulance Victoria.36 The Committee is chaired by a representative of the Shire.37

- The aim of the Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Plan prepared by the Committee:

is to capture municipal level multi-agency emergency management arrangements for the mitigation of, response to and recovery from all emergencies, as well as capture arrangements for specific emergency risks, where arrangements differ at the municipal level from those already captured in state and regional level plans.38

- Notably, aside from listing several landslides in an appendix of incidents since 2012, there are no other references in the Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Plan to landslide hazard and risk.39 In his evidence, former acting CEO of the Shire, Mr Oz, said that the Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Plan did not assess landslide as a stand-alone hazard because:

it is generally assumed that a landslide is a secondary event that occurs following a significant weather event, such as large rainfall within a short period or earthquake.40

- This assumption does not have regard to the broader range of preparatory risk factors that may need to be considered and managed in landslide management, including geomorphological and anthropogenic factors.

In a municipality that has known areas highly susceptible to landslide and that has a history of landslides impacting the community, the omission of landslide as a standalone hazard in the emergency plan needs to be examined by the Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Planning Committee.

Finding

The Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Plan does not identify landslide as a standalone hazard.

The approach in the Shire stands in contrast to the approach taken in other local government areas in Victoria. Many other municipal committees have specifically identified landslide or landslip as a key risk in their municipal emergency management plans. This includes the municipal emergency management plans in the Alpine Shire, East Gippsland Shire, South Gippsland Shire, Yarra Ranges Shire, Frankston Shire, Murrindindi Shire, Baw Baw Shire, Indigo Shire and Colac Otway Shire. While the Surf Coast Shire’s Municipal Emergency Management Plan 2023-26 does not identify landslide as one of its six highest risks across the municipality, the plan does identify landslide as a key risk for its communities of Aireys Inlet, Anglesea, Lorne and Torquay.41

Recommendation 19: Emergency management plans The Board of Inquiry recommends Victorian regional and municipal emergency management planning committees, including the Southern Metropolitan and Mornington Peninsula Committees, review their emergency management plans to ensure that landslide risk management is appropriately addressed. This includes reviewing and updating previous risk assessments, and where landslide risk is identified, water corporations should be represented on the committee.

The VicSES landslide plans

- In its coordination role to facilitate the development of emergency plans, the VicSES prepared a State Landslide Hazard Plan in 2018.42

- In 2019, the VicSES released the Central Region Emergency Response Plan – Landslide Sub-Plan, which is adapted from the State Plan and covers the Mornington Peninsula.

- These plans are emergency response plans only.

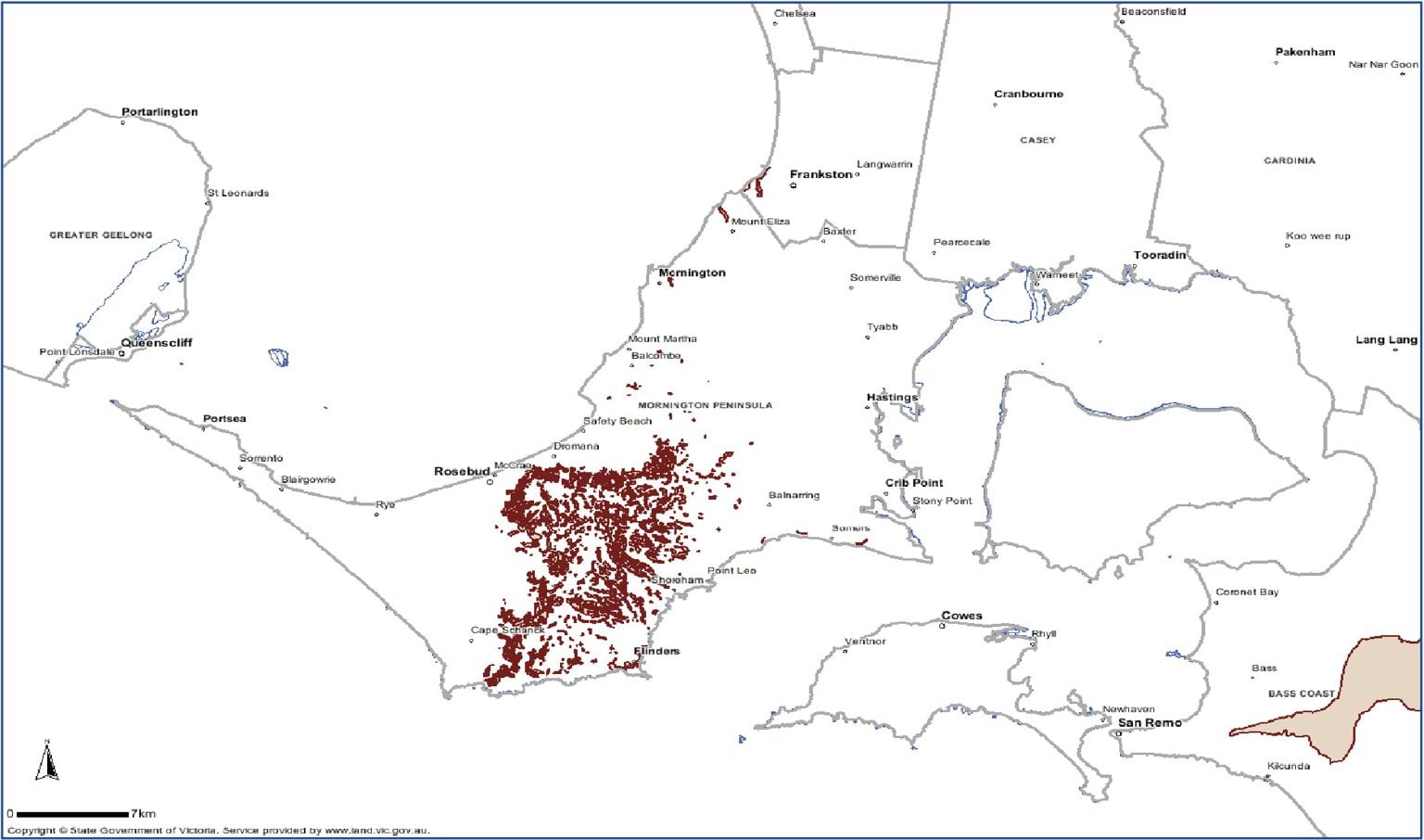

- Problematically, the Central Region Response Plan identifies “areas of concern” for landslide risk management as those areas identified in the EMO schedules of municipal planning schemes.43 As set out in Figure 8.2, it includes the following for the Mornington Peninsula:

FIGURE 8.2: THE MAP OF SOUTHERN METRO REGION – SHIRE OF MORNINGTON PENINSULA AND CITY OF FRANKSTON COUNCIL DETAILS EMO LOCATIONS, WITH AREAS OF CONCERN HIGHLIGHTED IN RED.44

As can be observed in the map, areas in the Shire that had known landslide susceptibility (including the location of the McCrae Landslide and the November 2022 landslides) are not highlighted in red. This is because those areas are not included in the EMO schedules in the Mornington Peninsula Planning Scheme.

Finding

The VicSES Central Regional Emergency Response Plan – Landslide Sub Plan does not identify areas in the Shire with known landslide susceptibility.

- The Board of Inquiry was informed that the VicSES Central Regional Emergency Response Plan – Landslide Sub Plan is to be reviewed following the review of the State Landslide Hazard Plan.45 As noted earlier, the latter review is now complete and the VicSES is developing a statewide landslide sub-plan to the SEMP.

Identifying landslide susceptibility and assessing risk

- Information plays a critical role in the identification of risk. Once risk is identified, it can then be managed.

- There is no detailed statewide data of landslide susceptibility in Victoria.

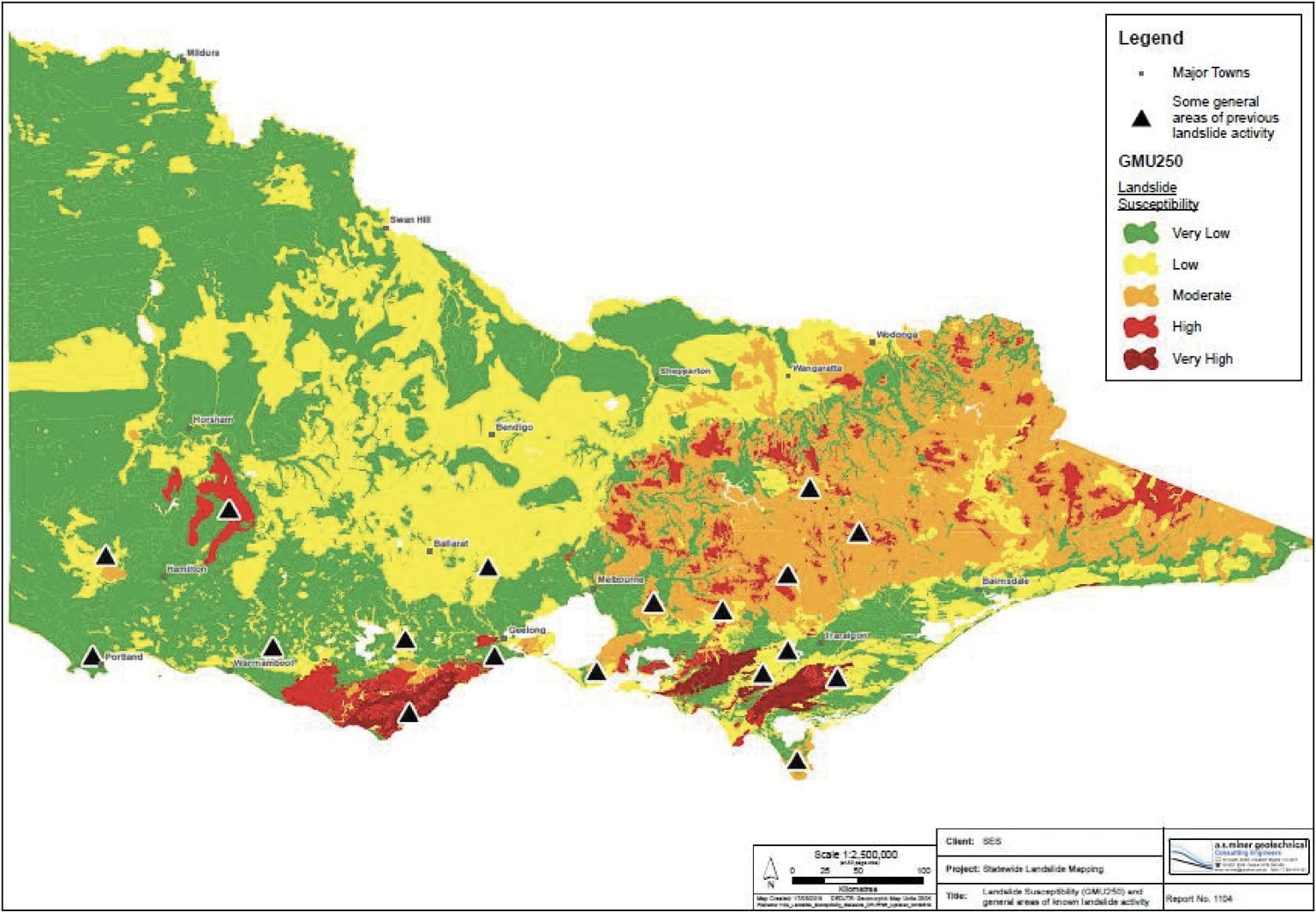

- In 2018, the former Victorian Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources developed a high-level overview of landslide susceptibility across Victoria using a spatial dataset of the geomorphology of Victoria (see Figure 8.3) for the purpose of highlighting potential landslide risk in the VicSES’s State Landslide Hazard Plan (2018).46 The map, however, is general and does not contain sufficient data to properly understand landslide risk and design responses to it.

FIGURE 8.3: VICTORIA’S LANDSLIDE SUSCEPTIBILITY.47

- Additional work has also been undertaken by government agencies where landslide impacts the management of other hazards. For example, the Board of Inquiry was provided with research commissioned by the former Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, which included heat maps of landslide risk following bushfires as part of a project known as Mitigating extreme post-fire hydro-geomorphic risk in Victoria.48

The Board of Inquiry requested information from a range of local councils about landslide risk mapping. The responses revealed that a small number of local councils have procured geotechnical mapping of landslide susceptibility in their area. Of the 21 councils who provided information to the Board of Inquiry, six indicated that they had procured comprehensive mapping of landslide risk in their local government area to assist in designing and implementing EMO schedules. These are Colac Otway Shire Council, Frankston City Council, Greater Geelong City Council, Manningham City Council, Northern Grampians Shire Council and Surf Coast Shire Council. A further two — Casey City Council and Whittlesea City Council — have completed site-specific assessments. Councils responded that the most significant barriers to undertaking mapping, were funding (62%), competing priorities (43%), complexity (19%), lack of technical expertise (19%).

Finding

There is no complete statewide mapping of landslide susceptibility available in Victoria.

- Victoria is not unique in this regard. Within Australia, Tasmania is the only state to have undertaken statewide mapping.49

- The New South Wales State Disaster Mitigation Plan notes that there is no consolidated statewide understanding of future landslide risk and commits New South Wales to “a data roadmap and research plan to continuously update data gaps on landslide risk”.50

- There is limited data of different kinds available in relation to landslide susceptibility across Australia.

- Commonwealth agency Geoscience Australia provides an online inventory of landslide incidents across Australia. However, updates to the inventory ceased in June 2018.51

- Research institutions have also sought to examine landslide data and model susceptibility. There is, for example, the University of Wollongong’s geographic information system-based Landslide Inventory and Landslide Susceptibility Modelling across the Sydney Basin.52 However, this is very localised data.

- With EMOs being one of very few publicly available sources of information about landslide susceptibility in Victoria, the Board of Inquiry was told that some agencies have turned to EMOs to inform their asset and service planning. For example, and as set out earlier, the Central Region Emergency Response Plan – Landslide Sub-Plan, which covers the Mornington Peninsula, used the EMO schedules in the region to identify areas of landslide concern.53 Similarly, SEW informed the Board of Inquiry that it uses EMO to inform capital works planning.54

- The problem with this approach is that not all areas susceptible to landslide are subject to an EMO. This was the case in relation to the location of the McCrae Landslide and the earlier landslides in November 2022.

- It is further noted that there is no requirement to regularly review the data that underpins an EMO. Underlying data can be decades old and in some cases it may not even be available. One council informed the Board of Inquiry that the risk assessment underlying an EMO was not available because it had not been transferred during the amalgamation of councils.55

- An additional problem with using EMO schedules as an indicator of landslide risk is that there is no agreed risk threshold, which means that some councils may use a higher threshold than others when identifying areas to be the subject of an EMO.

- However, there are alternatives to statewide mapping of landslide susceptibility. New Zealand has an online geotechnical database which was designed by several organisations. It contains geotechnical testing data uploaded by researchers, councils, engineers and developers in New Zealand. The estimated value of the database is more than NZD$500 million and has more than 7,000 users.56

- Sharing data will support a more comprehensive understanding of landslide susceptibility and thereby assists in decision making about the management of landslide risk.

In addition to data about landslide susceptibility, risk assessments also have a critical role to play. While data may highlight landslide susceptibility, risk assessments explicitly involve identifying exposure and vulnerability. Thus, risk assessments will assist decision-makers to understand priorities and the steps required to mitigate the risk of landslides.

Recommendation 20: Addressing data gaps on landslide risk The Board of Inquiry recommends the Victorian Government develop and implement a project that addresses data gaps on landslide risk. As part of the project, the Victorian Government should explore options for how landslide risk data can be shared and made broadly accessible, including by those living in areas with landslide risk for use in mitigating and managing the risk.

Consideration should be given to all options, including:

a. the creation of an online data resource;

b. engaging with Geoscience Australia, to explore opportunities, such as a partnership, aimed at resuming online data collection of Victorian landslides which was ceased in 2018;

c. the provision of technical or financial assistance to local government authorities where necessary; and

d. statewide mapping of landslide susceptibility, in coordination with relevant government departments.

Improving preparedness for landslides

- Emergency Management Victoria’s Preparedness Framework addresses how to mitigate, plan, prepare, respond to, and recover from, emergencies. Under that framework, emergency preparedness includes training, community education, information sharing and early warnings.

- Throughout the Board of Inquiry’s investigations, it was clear that there was little to no focus on strengthening preparedness for landslides following the landslides in McCrae in November 2022.

- The Board of Inquiry did not see any evidence of residents, businesses or service providers in the McCrae area receiving any support to be better informed or prepared in relation to the risks from landslides.

- Victoria’s emergency management arrangements centre around the principle that disaster risk reduction and resilience are shared responsibilities. The Australian Government’s National Disaster Risk Reduction Framework observes that shared responsibilities can only be effective where information about risk is also shared.57

- In the case of McCrae, risk information was not shared by relevant parties. The lack of information sharing and learning following the 2022 landslides led to limited local preparedness for the further landslide events of 2025.

The recommendations below reflect the Board of Inquiry’s view that there is significant scope for improvement in that respect.

Recommendation 21: Shire landslide training and guidelines The Board of Inquiry recommends the Shire arrange appropriate training and develop guidelines for relevant staff about local landslide risk, mitigation and management. Recommendation 22: Community information events The Board of Inquiry recommends the Shire arrange appropriate community information events to educate residents, business owners and service providers about local landslide risk, mitigation and management in order to support them in identifying and reducing risks on their land. - Unlike the range of tools available to engineers and builders to support them in advising, designing and implementing mitigations for landslide risk,58 there are limited materials and information currently available to support the community, or those working in emergency management and essential service delivery.

- In the case of residents, limited information is currently published by the Victorian Government about steps residents can take before a landslide. Community advice broadly focuses on what happens once a landslide is happening or has occurred.59

- Comparatively, other states such as Tasmania and Queensland provide information about types of landslides, warning signs that residents should look out for, and how residents can alert authorities before an event takes place.60

- The Shire informed the Board of Inquiry that it considers community education should include:

- information about the causes of landslides and landslips;

- how to mitigate and manage the causes of landslides and landslips, including:

- appropriate water use and management of water on and near the land;

- appropriate retention and propagation of vegetation, including large gum trees;

- minimising disturbance to the land through building activities;

- planning for the occurrence of a landslide or landslip (e.g. evacuation plans);

- information on how to monitor land for early signs of a landslide or landslip;

- directions on the appropriate authority to whom the occurrence of a landslide;

- landslip on private land should be reported; and

- what to do following a landslide or landslip.61

- As set out in Recommendation 22 above, the training and community information events the Board of Inquiry is recommending should include the topics outlined above, in addition to content about landslide risk in the municipal area.

- The limited information presently published by the Victorian Government about landslide mitigation and preparedness will be addressed through the preparation of the landslide sub-plan to the SEMP and updates to existing VicSES plans. Hazard sub-plans to the SEMP are made available to the public on the Emergency Management Victoria website. The intended audience is government, businesses, the broader Victorian community and primary agencies with responsibilities within the emergency management sector.62

- In conjunction with the preparation of the landslide sub-plan to the SEMP, it is expected that existing emergency management training programs and preparedness forums will be updated with more specific landslide information. Emergency Management Victoria and the VicSES both manage extensive emergency training programs and Emergency Management Victoria runs an annual critical infrastructure sector resilience forum and annual preparedness briefings with industry.63

- The Inspector-General for Emergency Management is also undertaking a review of statewide all-hazards community preparedness programs as well as a review of local government emergency management training.64 This work may include advice on these matters, including for local government.

- The Board of Inquiry notes that in updating educational materials and advice within Victoria, there is no shortage of expertise across Australia that government can draw upon. Australia’s academic and research institutions are well-advanced in landslide research and those who spoke to the Board of Inquiry were generous in sharing their insights as to how to keep communities safe. There is, for example, the University of Melbourne’s work on early prediction of slope failure,65 the University of Wollongong’s landslide inventory and susceptibility modelling,66 and the University of Newcastle’s rockfall hazard assessments.67 Geoscience Australia also seeks to support the community with data and advice on the vulnerability of the built environment and real-time monitoring and analysis. Several non-government organisations have also sought to provide the community with advice about nature-based mitigation strategies such as deep-rooted vegetation and bioengineering.68 Landcare New South Wales is one such organisation.

- The VicSES’s State Landslide Hazard Plan (2018) also contains useful information, including safety messages in relation to the threat of landslides. The State Landslide Hazard Plan (2018) sets out when the threat of a landslide becomes an emergency.69

- Regrettably, the growing threat of a landslide in McCrae after 5 January 2025 was not appropriately treated as an emergency, and, as such, was not referred to the VicSES before the threat materialised on 14 January 2025. This meant that the VicSES did not respond to the emergency or lead the coordination of public information and warnings in that period, as provided for in the State Landslide Hazard Plan (2018).70

- Emergency preparedness inherently involves early detection and continuous monitoring. Local landslide early warning systems can be used to monitor specific slopes that have been pre-identified as being at risk of failure. Specific risk thresholds can then be tied to certain emergency actions.

Detection, monitoring and prediction typically rely on remote-sensing techniques that include aerial observation, laser scanning and ground-based interferometry.71 A range of commercial products are available. Companies such as GroundProbe provide geohazard real-time monitoring.72

Recommendation 23: Early identification of landslide risk The Board of Inquiry recommends the Victorian Government, local councils and relevant stakeholders work together to identify pathways for early identification of landslide risk and ensure escalation processes and procedures are well understood. This is a matter which may be most appropriately addressed as part of the development of the landslide sub-plan to the SEMP.

Lessons management

- Lessons management is an important part of assurance and continuous improvement in emergency management, as with other areas of policy and practice.

- Debriefs, after action reviews, community surveys and independent evaluations all offer different strategies for collecting learnings, observations and insights. As the Australian Institute of Disaster Resilience notes:

Australia’s safety and security depends on our collective ability to learn from experience, manage the knowledge gained and develop learning organisations that can adapt to deal with current, emerging and unexpected threats. Organisations need a lessons capability that adequately resources the collection, analysis, distribution and sharing of lessons in a way that ensures action is taken to effect change.73

- The Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Plan refers to the role of lessons management. It notes “the committee regularly undertakes a review process to improve risk assessments, analysis of lessons learned from events, changes to exposure and vulnerability and changes in the nature (frequency and severity) of hazardous events”.74

- The Board of Inquiry received no evidence that the Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Planning Committee debriefed about the November 2022 landslides in McCrae or discussed landslide risk in any detail. This is despite the fact that the Shire’s MBS had issued Emergency Orders to the owners of multiple affected properties.

- A debrief or review could have resulted in actions being taken prior to the next, more significant, landslide that occurred in the same area on 5 January 2025. The absence of an EMO could have been discussed. The need to seek further data and information about landslide susceptibility and risk in the local government area could have been considered. A debrief could have identified a need for more timely communication with residents about risk and mitigation. Landslide may have ultimately been identified as a “principal emergency risk” to be included in the Emergency Management Plan. These opportunities were missed.

- Fortunately, debrief opportunities were not missed again following the McCrae Landslide. Mornington Peninsula Municipal Emergency Management Planning Committee members did discuss the landslide incident at the 21 February 2025 meeting.75

It is important that municipal emergency management planning committees take responsibility for debriefing and learning. While the Inspector-General for Emergency Management has a review role, they only undertake incident reviews at the request of the Minister. This makes municipal-level reviews a crucial tool for learning from past events.

Recommendation 24: Emergency management planning committee debriefing The Board of Inquiry recommends municipal emergency management planning committees review their procedures to ensure that, following landslide incidents there is appropriate debriefing which includes actively considering opportunities to improve mitigation, planning and preparedness measures.

8.2.1 Case study: what does an integrated and coordinated approach to mitigation look like? Learning from Victoria’s approach to coastal erosion

- The Victorian Government is currently running a statewide monitoring program for coastal erosion that draws on data and analysis from drone surveys, satellite imagery and photographs from the community using CoastSnap (see case study below).76

- The program is an invaluable example of a comprehensive statewide approach to a hazard similar to landslides. The Board of Inquiry received extensive evidence of detailed methodologies, plans, data, tools and guidelines designed and delivered by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (DEECA) and its portfolio agencies in partnership with academics, industry and community to manage the risks arising from coastal erosion.

- The Marine and Coastal Strategy (2020) provides the policy framework that guides activity and also identifies specific actions to mitigate the risk of coastal erosion including:

- collecting and sharing information to inform hazard mapping and projections, erosion advice, emergency responses and adaptation planning;

- delivering priority coastal hazard data and applications to fill known gaps and support planning across public and private land;

- establishing coastal erosion advisory support; and

- reviewing and strengthening coastal hazard warning services.77

- Underpinning this work is a shared understanding of risk. In 2023, DEECA published the Victorian Coastal Cliff Hazard Assessment,78 a digital dataset consisting of multiple spatial layer outputs from modelled erosion (cliff instability) and risk assessment scenarios. This provides a comprehensive statewide understanding of areas susceptible to coastal erosion.

- The Victorian Government has also established the Victorian Coastal Monitoring Program.79 This is a field monitoring and knowledge management program that provides coastal managers and communities with information about coastal processes and hazards and enables them to make informed decisions about how best to manage the risks. Importantly, it also involves the community in the process of collecting data. Residents can participate through the Citizen Science Drone Program or share coastal photos via CoastSnap (a global citizen science project founded by the University of New South Wales and New South Wales Department of Planning, Industry and Environment) to complement data from satellite and drone imagery.80

- The Victorian Coastal Monitoring Program is supported by the following two tools that assess erosion hazards:

- the erosion warning indicator used to assess a site overall and compare sites; and

- the erosion hotspot detector used to automatically identify and assess high erosion areas in greater detail.81

- The indicators ensure there is a single product output from the Victorian Coastal Monitoring Program that summarises the current state of all regularly surveyed sites with regard to coastal erosion. It serves as a reference for coastal land project managers, consultants and academics to, for example, provide an overview of a site prior to conducting a detailed hazard assessment.

- DEECA also administers Victoria’s Resilient Coast Grants Program which provides funding for organisations for strategic coastal hazard risk management and adaptation aligning to one or more stages of Victoria’s Resilient Coast Adapting for 2100+.82

- DEECA’s comprehensive and well-regarded statewide program to manage the risk of coastal erosion offers insights for managing landslide risk.

In a changing climate with more extreme, severe and prolonged weather events, there could be an increased risk of landslides in Victoria.

Recommendation 25: Obtaining insights and expanding other programs The Board of Inquiry recommends the Victorian Government consider how insights from the Victorian Coastal Monitoring Program could be applied to landslides and explore options to expand or build on the program, including by monitoring areas identified as being highly susceptible to landslides.

8.3 Land use planning

- Land use planning is a key strategy to minimise the risk and consequences of landslides.

An overview of Victoria’s land use planning system

- The Planning and Environment Act 1987 (Vic) (Planning and Environment Act) serves several purposes. It:

- establishes a framework for planning the use, development and protection of land in Victoria;

- contains procedures for preparing and amending the Victoria Planning Provisions and planning schemes;

- sets out the process for obtaining permits under planning schemes; and

- defines the roles and responsibilities of councils, government departments and others involved in the planning system.

- It does not precisely define the scope of planning. The detail is in instruments made under the Planning and Environment Act, including in the Victoria Planning Provisions, planning schemes, regulations and Ministerial directions.

- The Victoria Planning Provisions are a comprehensive set of planning provisions for Victoria. They are not a planning scheme and they do not apply to any land. The Victoria Planning Provisions are a statewide reference document used as required to develop a planning scheme. They are a statutory device to ensure that consistent provisions for various matters are maintained across Victoria and that the construction and layout of planning schemes is always the same.83

- A planning scheme is a statutory document that sets out objectives, policies and provisions relating to the use, development, protection and conservation of land in the area to which it applies. A planning scheme regulates the use and development of land through planning provisions to achieve those objectives and policies. The provisions in a planning scheme will include standard zones and overlays. Some of these zones and overlays will include local provisions as schedules to the zone or overlay.84

- The administration and enforcement of a planning scheme is the duty of a responsible authority. In most cases this will be a council, but it can be the Minister administering the Planning and Environment Act or any other person whom the planning scheme specifies as a responsible authority for that purpose. A council will usually act as both the planning authority and responsible authority.85

- All land is subject to zoning. The planning scheme zones land for particular uses, for example, residential, industrial, commercial. The zones are listed in the planning scheme and each zone has a purpose and set of requirements for use. A planning scheme sets out if a planning permit is required for proposed works and the matters that the council must consider before deciding to grant a permit.86

- The planning scheme map may show that land is subject to an overlay and zoning. However, not all land is subject to an overlay and some land may be subject to more than one overlay. If an overlay applies, the land will have some special feature such as a heritage building, significant vegetation or flood risk. The overlay information will indicate if a planning permit is required for the construction of a building or other change to the land and set out requirements for subdivision and buildings and works that apply in addition to the requirements of the zone.87

How is landslide risk managed in the planning system?

- Planning tools are particularly important in the context of landslide risk. Like many hazards – such as bushfire and flood – poor planning can increase community vulnerability and exposure through development in high-risk areas. Uniquely, poor planning can also be a preparatory factor for landslides. While individual buildings may be able to manage landslide risk through engineering solutions, poor planning for urban development may disrupt soil cohesion and change water pathways, destabilising areas of land and creating or exacerbating landslide risk.

- There are two primary mechanisms within Victoria’s land use planning system that seek to manage landslide risk.

- The first is the statewide policies contained in the Planning Policy Framework.

- The second is the EMO, which has already been the subject of much discussion in this Report.

- These two mechanisms are supported by a range of broader tools which can also assist to mitigate landslide risk, such as the vegetation protection overlay and stormwater management planning.

- Starting with the Planning Policy Framework, the policies contained in the Planning Policy Framework are incorporated into the Victoria Planning Provisions and all planning schemes.88

- Clause 13.04–2S of the Planning Policy Framework sets an objective to protect areas prone to erosion, landslip or other processes of land degradation, including:

- identifying areas subject to erosion or instability in planning schemes and when considering the use and development of land;

- preventing inappropriate development in unstable areas or areas prone to erosion; and

- promoting vegetation retention, planting and rehabilitation in areas prone to erosion and land instability.89

- Planning authorities (usually councils) are required to give regard to those objectives in designing and managing their planning schemes, and when determining applications for planning permits.

- While consideration of the objectives in cl 13.04–2S is mandatory, there is flexibility within the system. As a result, some planning schemes contain general policy statements addressing erosion and landslides, while others have dedicated local policies dealing specifically with those matters. This enables planning authorities to take steps proportionate to local conditions and risk.

- Turning now to the second mechanism, the EMO is one of several standard overlays with statewide application within the Victoria Planning Provisions.90 It aims to “protect areas prone to erosion, landslip, other land degradation or coastal processes by minimising land disturbance and inappropriate development”.91

- Where an EMO applies to land, building works, vegetation removal and subdivision all require a permit, unless an exemption is listed. When deciding an application, the responsible authority must consider a range of requirements including stabilisation measures, measures to manage water runoff and site drainage, the extent of soil disturbance, and whether the building works themselves are likely to result in landslide.92

Limitations on the efficacy of the planning tools

- It is evident that there are limitations on the ability of current statewide planning policies and tools, particularly the EMO, to appropriately and comprehensively manage landslide risk.

- The Minister for Planning referred the Board of Inquiry to several concerns and issues with the design and application of the EMO identified by the Department of Transport and Planning during a desktop review.93 The Minister acknowledged that those concerns present a case for improving how the EMO operates.94

- It is appropriate to now discuss some of the Minister for Planning’s concerns and others also identified by the Board of Inquiry.

Data on landslide risk

- The first limitation on the effectiveness of the EMO identified by the Board of Inquiry is the availability of data.

- As already discussed, there is presently no statewide data on landslide susceptibility or statewide assessment of landslide risk. For the planning system, this has meant that councils, as the relevant planning authorities, need to acquire relevant data to identify areas to be subject to the EMO. This often involves procuring expensive geotechnical assessments.

- As also discussed earlier, only six of the 21 (29%) councils who responded to questions asked by the Board of Inquiry had mapped landslide risk. The biggest impediments raised to mapping and implementing an EMO by councils were funding (63%), competing priorities (42%), complexity and/or a lack of clarity around requirements (16%) and a lack of technical expertise (11%). Several councils indicated they had not mapped landslide risk as they did not believe their council had sufficient risk to warrant the investment.

- This approach to data collection can be contrasted to the situation in relation to the Bushfire Management Overlay. Bushfire risk is identified and verified through a mapping process managed by the Department of Transport and Planning, relevant fire agencies and local government. The Department of Transport and Planning prepares bushfire management overlay planning scheme amendments based on that mapping, and the Minister for Planning approves updates under s 20(4) of the Planning and Environment Act “generally every six months”.95

- The Shire is one council that has procured mapping of landslide susceptibility.96 As discussed in earlier Chapters of this Report, it did so many years ago and is presently updating this mapping.97 While the Shire did procure mapping, regrettably it did not then use the data to seek to update the areas covered by the EMO schedules.

- Where councils procure such data, there is no guidance as to how they should use it to assess risk, design appropriate planning controls or undertake mitigation measures. This means that land with the same level of risk included within an EMO in one council area but not included within an EMO in another council area, may be subject to different thresholds for mitigation measures.

- The Minister for Planning helpfully acknowledged in her submission to the Board of Inquiry that planning policy would be strengthened by practice notes and guidance specifically on landslide risk. The Minister noted that:

By comparison, the mandatory state-wide policies relating to coastal inundation and erosion ... and bushfire planning ... are more sophisticated and responsive to those known risks. These include, for example, guidance on hazard identification and assessment, a hierarchy of interventions, and benchmark metrics to assist decision-making.98

- This issue is not unique to Victoria. The New South Wales Disaster Mitigation Plan confirms that in New South Wales “there are no agreed processes to balance tolerable hazard risk with housing supply and development. This means there is currently no agreed criteria and thresholds for what makes land ‘too hazardous’ for different types of development across all hazards”.99

- Nevertheless, there are useful examples across Australia of balancing local flexibility with greater consistency and sound decision making in the absence of landslide mapping data. Planning authorities in other States have adopted approaches to risk tolerance that minimise the level of discretion and reliance on regular and costly landslide mapping data.

- In Queensland, local government authorities apply Landslide Hazard and Steep Slope Overlay Codes, which form part of their planning schemes. Instead of procuring costly landslide susceptibility data for the purpose of identifying areas to be the subject of the overlay, a planning authority can simply identify and include those areas with a slope gradient of at least 15%.100

As Mr Paul, explained in his evidence to the Board of Inquiry, slope angle is a critical risk factor in landslide susceptibility. He went on to state that “in a general sense, the steeper the slope the more susceptible it might be to sliding”.101

Finding

The Victorian planning system allows for widely inconsistent approaches by local planning authorities to the identification and management of landslide susceptibility and risk.

Using a single overlay for both landslide and coastal erosion

- The next limitation to be discussed concerns the inclusion of coastal erosion and landslide within a single overlay. Victoria is one of few jurisdictions to have a single overlay covering both landslide and coastal erosion. On the Mornington Peninsula, this means that the mountainous areas of Red Hill and the coastal cliffs of Flinders are covered by the same overlay, despite different preparatory risk factors existing, which in turn require very different mitigation measures.

- The lack of distinction between these hazards in the Victoria Planning Provisions makes it difficult to assess whether the overlay is effective in managing landslide risk. It also makes it challenging to set benchmarks and targets, a matter noted by the Minister for Planning.102

- There is also potential for the community to misunderstand the nature of the overlay. This is especially so where the EMO does not identify the reason it is applied to certain land. A desktop review of the EMO in 2023 by the former Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning found that where an EMO was applied, there was usually limited information within EMO schedules to explain why it had been applied to a specific area.103

- Queensland, New South Wales and Tasmania all refer to landslide risk in the name of the relevant overlay and distinguish landslide risk from other types of erosion.

Conflicting planning control needs for hazards

- A third limitation on the effectiveness of the EMO is the conflict between planning controls for different types of hazards and a lack of guidance on navigating the issue. Largely, the planning system seems to presume exposure to a single hazard at a time. In the case of McCrae, this conflict was most evident between bushfire and landslide risk.

- Vegetation is critical to risk mitigation for landslide. However, the Bushfire Protection Exemptions within the Victoria Planning Provisions allow landowners to clear vegetation around their property or maintain defendable space for bushfire protection without a planning permit.104 This may be the case even where the land is at greater risk of landslide than bushfire. As the Shire submitted to the Board of Inquiry, in relation to these exemptions, “their general and strict application can have an inadvertent adverse impact on the prevention and management of landslides”.105

- The converse is true when an application is made for a planning permit in respect of an area subject to an EMO. Such applications are often accompanied by an opinion from a geotechnical engineer about the risk to life from a landslide event. They do not address other hazards which might be created from the imposition of conditions to mitigate the risk of landslides. Such conditions (e.g. vegetation conditions) may create other hazards, such as those related to bushfires. There are no practice notes or guidelines to assist planning authorities with such issues.

- A strategy that could be considered to ensure an all-hazards approach is for planning authorities to assess societal risk.

- Societal risk concerns the potential adverse impacts and consequences that hazardous events or disasters can have on a community, population or society. It encompasses the likelihood of such events occurring and the extent of harm that they could cause to people, property, infrastructure, the environment and the overall wellbeing of the affected population.106 It provides a potential pathway to consider the interrelationship between different hazards as well as the long-term impacts on communities.

Mr Pope gave evidence that current geotechnical reports use risk to life assessments that assess risks to individuals, but the standards also provide opportunities to consider broader societal risk.107 New Zealand’s Landslide Planning Guidance: Reducing Landslide Risk through Land-use Planning (2024) considers societal risk alongside local personal risk, annual individual fatality risk and annual property loss/risk.108

Finding

Planning controls for different hazards can be in conflict, such as vegetation management for bushfire risk and landslide mitigation measures. Victoria’s land use planning system does not assist planning authorities to navigate concurrent and interdependent hazards.

Timeliness of updates to areas covered by an EMO

- The Board of Inquiry received evidence from Mr Simon, Acting Director Planning and Environment at the Shire, that the most recent update to the Shire’s EMO schedules had taken six years.109 By the time the update came into effect in January 2025, the landslide mapping that had informed it was more than 10 years old.

- While this was certainly at the upper end of timeframes, the Department of Transport and Planning confirmed that the full process for an amendment that is publicly exhibited and referred to Planning Panels Victoria typically takes at least one year. The Department of Transport and Planning informed the Board of Inquiry that in the last three years the median time for a medium complexity planning scheme amendment in Victoria was 378 days.110